I’m happy to announce that a paper of mine has been published in Linguistics Vanguard. It’s called “Interpreting the order of operations in sociophonetic analysis” and it’s a direct follow-up to a paper I wrote for the Penn Working Papers in Linguistics a couple months ago. While the PWPL paper showed that Order of Operations (OoO) matters, that we should be talking about it more, and that we should do our best to interpret others’ OoOs, it didn’t give any help as to how to interpret them. The main contribution for this follow-up paper then is to 1) arm researchers with knowledge of how to interpret order of operations and 2) justify the order I recommended in the PWPL paper.

Summary

To reiterate what I said when the PWPL paper came out, the idea for this paper got started when I was in the throes of data analysis and I noticed that reordering some of the processing steps resulted in different changes. I did a systematic study of OoO, presented it at NWAV49 in 2021, and published those results in PWPL. But it occurred to me that even if we all become diligent and report the OoO we used in our papers, we don’t really have the knowledge of how we’re supposed to interpret those orders. As I put it in the paper,

[I]t does little good if researchers are not familiar with how the order affects the overall results. A detailed methods section may explain that normalization happened before outliers were removed, but it is not currently clear what effect that order had on the results. How should a reader evaluate the results of one study that normalized the data before removing outliers against another study that transposed those two steps? This paper addresses this gap and explores in more detail the effect that some orderings are likely to have on the results of a study.

Perhaps phrase another way, what specifically is the effect of normalizing before removing outliers compared to removing outliers before normalizing? Do formants go up, down, or something more complicated? As I mention in footnote 1, this knowledge can be used as “cheat codes” to manipulate your data the way you want. Hopefully reviewers can spot this kind of hacking!

Anyway, so when I analyzed the same data 5040 times but with different orders of operation, I ended up with 5040 hypothetical analyses of the same dataset. Obviously, it didn’t make sense to consider every single one. So instead, I concentrated my efforts on 1) finding orders that produced identical results and 2) seeing what happens when I swapped two steps in the recommended OoO I have in the PWPL paper.

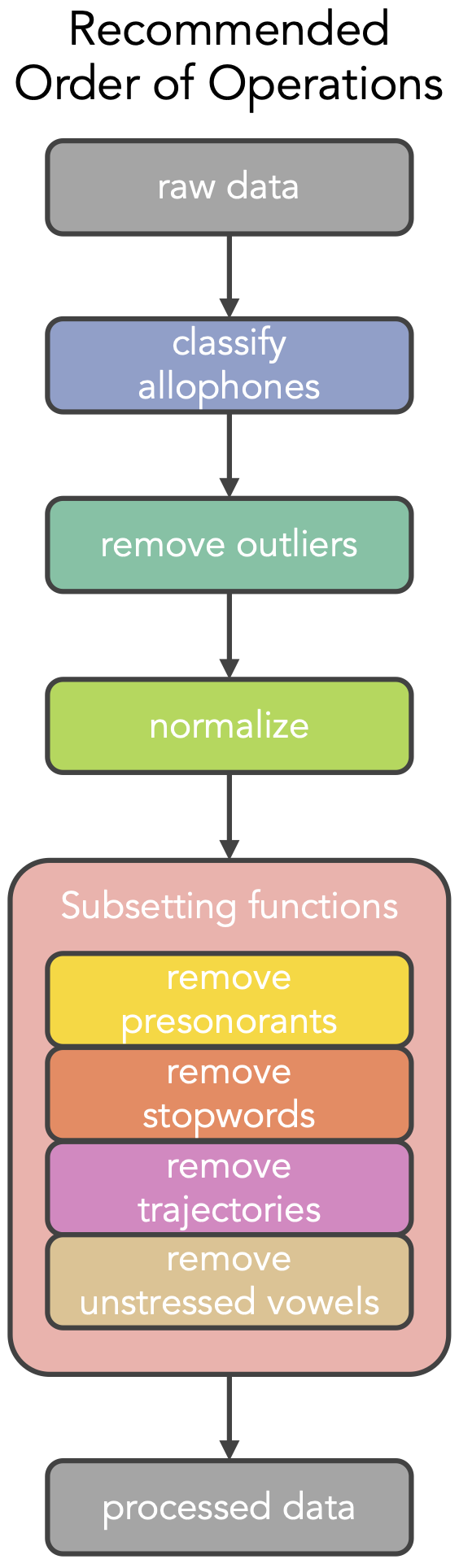

Here’s that recommended order (Figure 1):

Many of the orders produced identical results. This was mostly the result of various subsetting functions removing different groups of unwanted data, such as unstressed vowels, presonorants, stopwords, and vowel trajectories. This makes sense because, as I say in the paper,

The set of observations that are excluded in these steps is fixed: regardless of the normalization procedure, whether outliers have been removed, or how the vowels are classified, the exact same set of observations will be excluded each time.

These functions are all similar in that they remove data that is not needed or wanted for the current analysis, but is otherwise good. This similarity is visualized by clumping them together within a single block. I argue that because this is good data, it should only be removed at the very end of the pipeline, even after normalization.

So then I go and explore each pair of steps in my recommended order. Allophones should be classified before removing outliers because it just makes sense to do so. Also, failing to do so will make Pillai scores go up because you artificially draw two vowel classes together. Outliers should be removed before normalization because you don’t want outliers to mess up the normalization.

The trickiest part of the paper to understand is section 6 and Figure 4. I use it to show the interaction between normalization and subsetting. I recommend normalizing first. If you subset first and then normalize, the data is altered in kind of a weird way, especially if you’re doing Lobanov normalization. In the end I conclude that it’s better to normalize first with this justification:

One may argue that subsetting should happen before normalization so that comparisons across studies are more meaningful. It is true that a study that collects interview data will exclude many more tokens than another study that only elicits wordlist data. An argument can be made that by subsetting before normalization, what remains from the interview study more closely matches what is even collected in the wordlist study, and therefore the effect of normalization is more comparable between the two. However, a follow-up study of the interview data that happens to focus on something that was previously excluded, like vowel trajectories, will end up with a different input into the normalization step than the first study. There will be a difference between the normalized data in the first study and the normalized data in the second study. In other words, a single token of [æ] will have different normalized F1–F2 measurements between the two studies. This makes no sense since the token has not changed whatsoever.

However, I acknowledge that if speakers have markedly different sample sizes, normalization will affect them in different ways. I think this is more indicative of an imperfect normalization procedure than anything else. We just haven’t yet found a method that perfectly models the human ear. There is room to explore normalization procedures that perform better or worse when speakers’ datasets are not particularly comparable.

Conclusion

Anyway, I encourage you to read the paper. I enjoyed writing it. And now that I’ve closed up that loose end, maybe I can now go back to doing actual sociolinguistic research!