I’m thrilled to announce my latest journal article, “LTH Affrication: A sociolinguistic indicator in the American West”, co-authored with Jessica Shepherd, has been published in Journal of English Linguistics! Jess was an undergraduate at BYU and was an RA for me when we started this project. She is now a PhD student at Michigan State and is working on the MI Diaries project.

Summary

The phenomenon

I don’t remember when I first noticed the phenomena that we’re calling “LTH Affrication”, but sometime maybe five years ago I started hearing people pronounce words like health and stealth with some sort of pause between the /l/ and /θ/. In the manuscript, we transcribe it as a dental affricate [t̪͡θ]. I don’t think I’ve ever seen this mentioned in linguistics literature at all, so it’s kind of exciting to be the first to describe something!

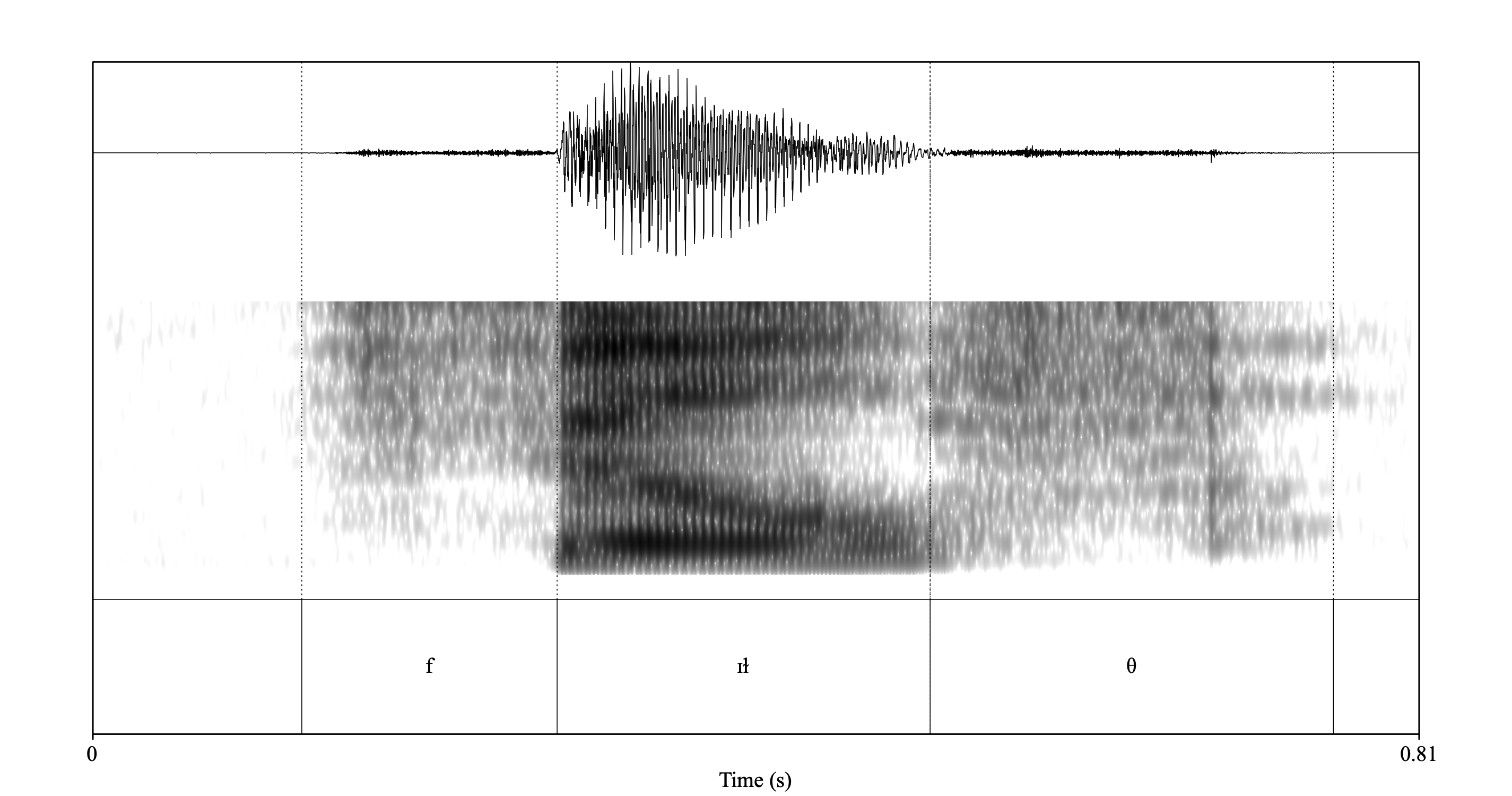

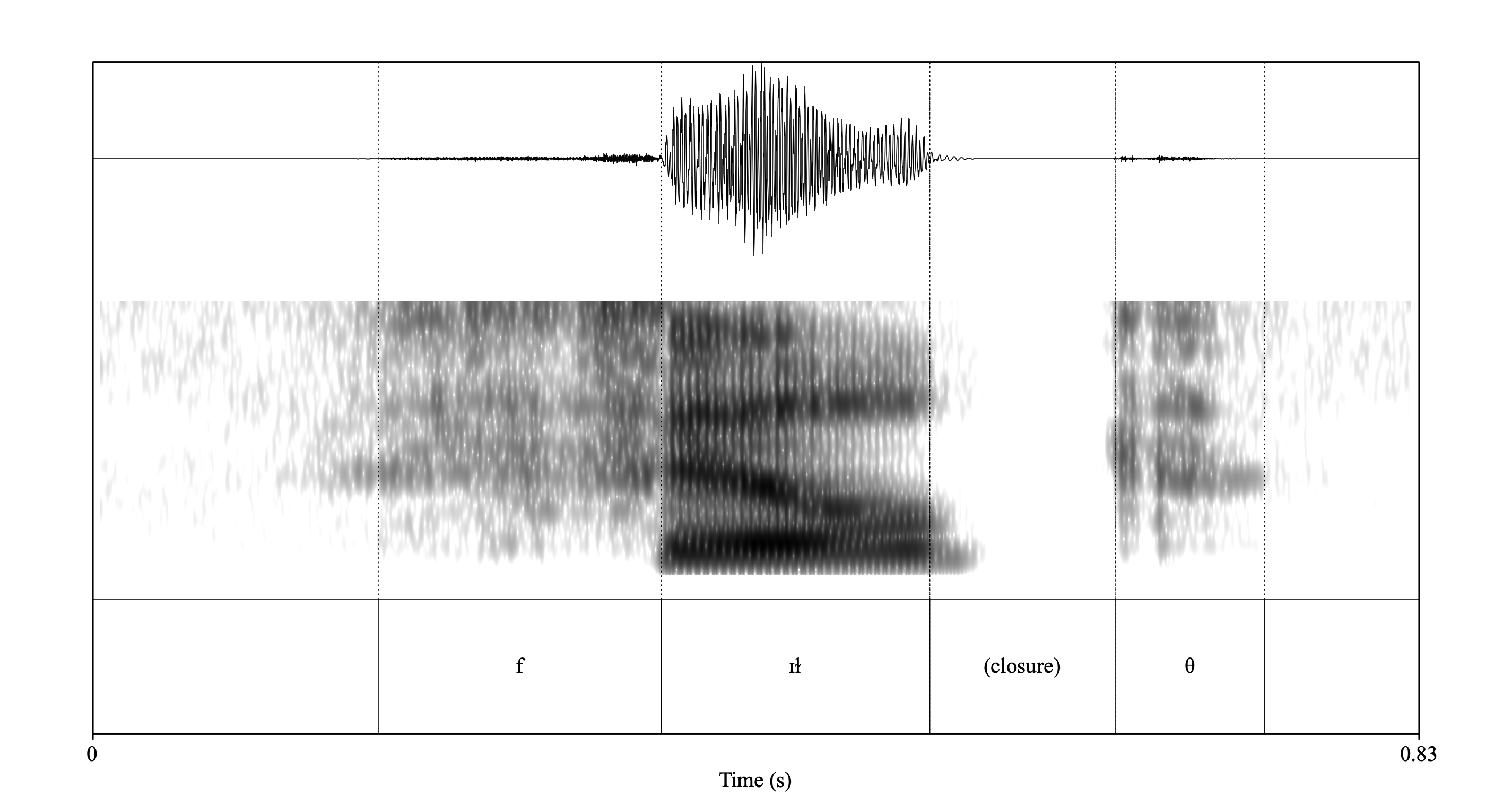

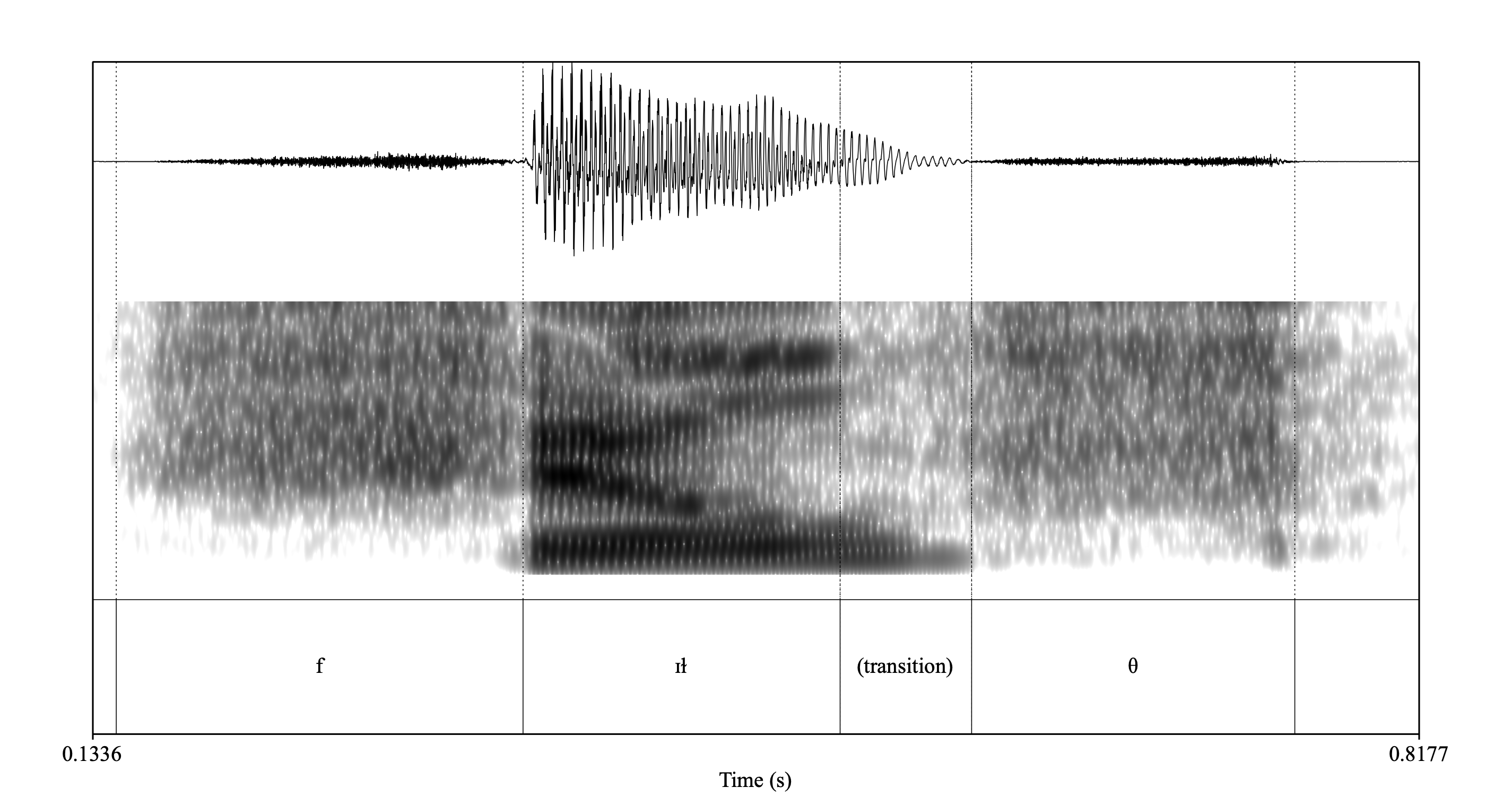

Here are the examples we showed in Figure 2 of the paper.

A clear example of no closure.

(“Jamie”, White, female, 1982, Latter-day Saint, Idaho Falls)

A clear example of closure.

(“Connie”, White, female, 1967, Latter-day Saint, Blackfoot Idaho)

An unclear case.

(“Melody”, White, female, 1982, Helena Montana)

As a bonus to you, dear blog reader, you can download this audio here.

At first, I thought it was some sort of [t]-insertion similar to what I occasionally hear in words like false and else. An earlier version of the manuscript called it t-excrescence, that word referring to a specific kind of insertion where consonant is inserted between two other consonants. When a reviewer pushed back on the obscure jargon term, we reconsidered the name. We eventually decided insertion implies a phonological process that we’re not fully committed to, and we instead opted for a more descriptive, phonetic name, affrication.

The study

Around the time I was hearing this affrication, I was starting two different data collection projects that involved wordlists. So I threw in a couple LTH words just to see what would happen. The data from one of these projects eventually became the dataset for this study and we got recordings from 265 people, mostly from the region we’re calling the Middle Rockies, which includes Utah, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming.

A surprising number of people—about a third—had LTH affrication! We didn’t expect it to be so high, so that was pretty cool for us. However, despite being so variable, none of the demographic variables we collected were significant predictors for whether someone had affrication or not. It seems to occur somewhat randomly across our sample. We take this as evidence that LTH affrication is an indicator in the Labov (1972:178–180) sense, which are linguistic variables that are socially invisible. We’ve scoured the internet for comments on English in the region and we have not found anybody saying anything about words with /lθ/, even though a third of people have it. It’s kinda cool to catch such an under-the-radar linguistic variable.

Focusing then on the 88 people who did have affrication, we looked at the duration of the closures in that affricate. Women, suburban-oriented people, and practicing Latter-day Saints had the longest closure durations. Age was not a significant predictor, but there is weak evidence that Utahns have longer durations too. So, there may be some social meaning involved in those durations (see Hallie Davidson’s work-in-progress on exploring that specifically!), which would be a cool thing to discover.

Theoretical implications

In the paper, we discuss at length the idea of infrequent phonological variables. LTH Affrication certainly qualifies: there are only about four commonly used words with /lθ/: health, wealth, stealth, and filth, plus their derived forms. We estimate that you might hear /lθ/ roughly once every 51 minutes of continuous speech. The only real way to study such infrequent variables is to elicit them directly with wordlists or reading passages. We compare this to /æɡ/- or /ɛɡ/-raising, which people have specifically mentioned not being able to study because of a lack of data. However, we observe that /æɡ/-raising in places like Washington State still have complex indexical fields, similar to more common variables like /æ/-lowering, /t/-release, and ING. If it takes fewer tokens to accrue such complex meanings, listeners apparently store rich sociolinguistic information with every instance of every variable, which is exactly what Exemplar Theory proposes.

We then talk about how LTH Affrication appears to be part of the Latter-day Saint religiolect. This is yet another example of how fortition generally is common among Latter-day Saint Utahns and we speculate as to why fortition would be used as a linguistic device to index one’s Latter-day Saint identity. Part of this is also tied up with the idea of suburban identity because most of the Wasatch Front, where 90% of Utahns live and is where the core Latter-day Saint culture is found, is one long stretch of suburbs. We also point out that former Latter-day Saints pattern more with people of other faiths, which not only strengthens the idea that LTH is associated with Latter-day Saints, but also acknowledges this group as distinct from practicing Latter-day Saints.

There are lots of places where insertion or affrication happens in English: empty, glimpse, pumpkin, el[t]se, prin[t]ce, ham[p]ster, warm[p]th, streng[k]th, and ten[t]sion. All of these have sonorants followed by obstruents. Are there communities that have such insertion or affrication in /lf/ (itself, golf, welfare), /lʃ/ (expulsion, convulsion, propulsion), /mf/ (emphasis, comfort, triumph), or /nθ/ (month, tenth, anthem)?

Anyway, it has been a fun paper to work on and I’m thrilled to finally see it in print.

Behind the scenes

I like hearing about the behind the scenes of others’ papers, so here’s that background on this one.

On September 8, 2022, Jess stopped by my office out of the blue, started chatting about things, looked through a lot of the data I had just collected a few months prior, and we got interested in LTH because she’s heard it before. I have in my notes that it was such a small topic that I wasn’t planning on doing a full publication on it, but because a student was interested in it, I changed my mind!

Later that month, we met again. Jess had reviewed what others have said about excrescence and we decided that closure duration was the thing we’d focus on. At the time we were considering English Language and Linguistics since we didn’t think we could make enough of a theoretical contribution for it to be in Journal of English Linguistics

By the end of Fall 2022, I had finished transcribing all the data and had gotten duration measurements. We had basically found the results that we presented in the paper. The methods and results sections of the paper were written.

In February 2023, I recoded all the data and got new duration measures since I noticed a bit of an error in how I did it before. The general findings were unchanged though. On February 10, 2023 I was in the zone and wrote about 1800 words, mostly in the literature review. By February 27th, we had a full manuscript.

In March 2023, we submitted to Language Variation and Change, but got a very fair desk reject. So we made some changes and on March 15th, submitted it to Journal of English Linguistics. I guess I was feeling good about the theoretical contribution that this makes.

We got our first R&R from them on August 17th, 2023, about five months after submission. However, it was terrible timing for both of us. I had just started parental leave so I wasn’t going to work on it for several months. And Jess had just moved across the country and was about to start her first year of her PhD program, so she wasn’t available to work on it either. We finally revisited the reviews in February 2024 and on March 15th, we resubmitted it to JEngL (exactly one year after our first submission).

We got a conditional accept on April 2, 2025 (12½ months after we submitted). I’m not quite sure why it took JEngL so long. We resubmitted on April 22 and got the official accept on May 2. It was published online today, June 17th.

So from initial idea to publication took about three years.

Bonus

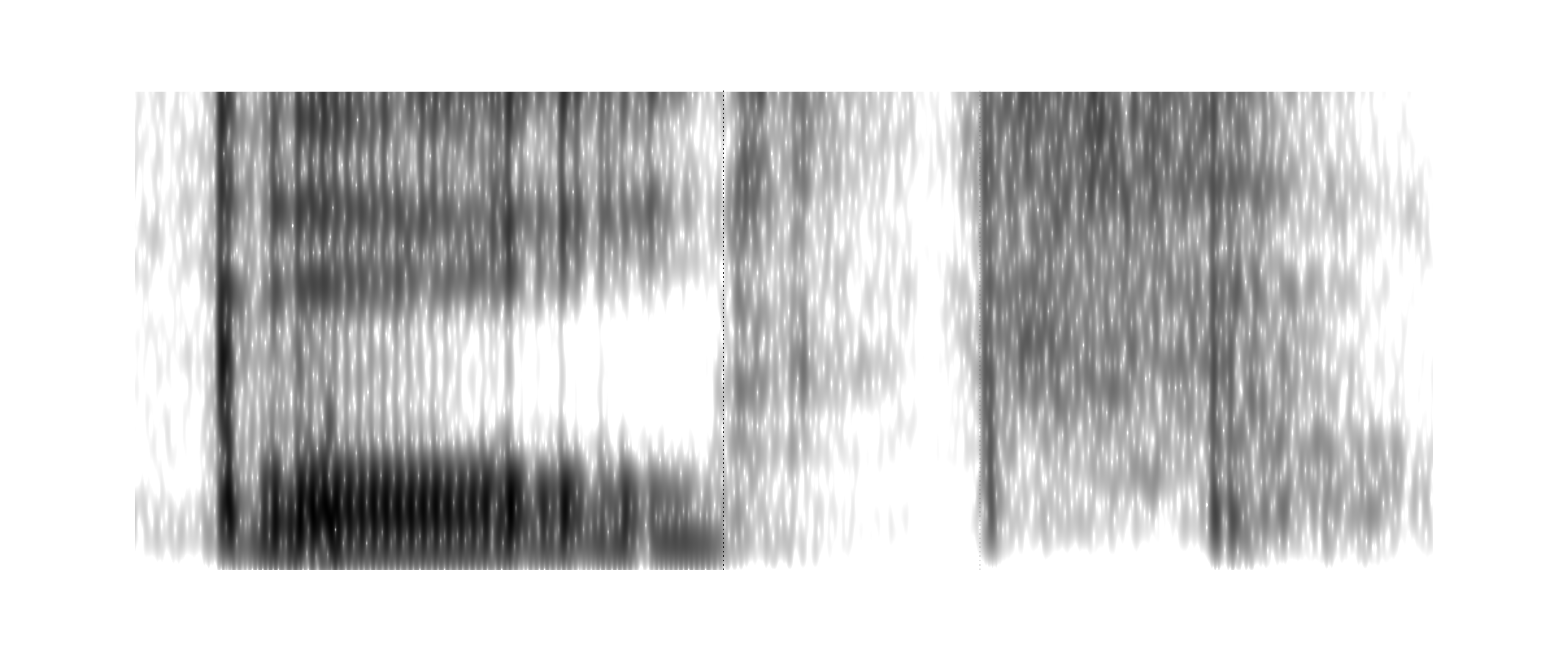

This is one of the coolest clips I have. Here is a recording and spectrogram of someone saying both. But, not only does she have [l] insertion in the word, saying it as if it were bolth, but she then has LTH-affrication on top of it!

both as [boɫt̪͡θ], with some creak.

(“Giselle”, White, female, 2001, non-practicing Latter-day Saint, Provo Utah)