Together with my co-authors, Lisa Morgan Johnson and Earl Kjar Brown, I’m happy to announce a new publication in Linguistics Vanguard!

A “Brief” Summary

The problem that sociophoneticians face when working with interview data—particularly recordings not originally intended for linguistic analysis like older oral narratives—is overlapping speech. When two people talk at the same time, it is usually impossible to get reliable formant measurements automatically. My impression is that that data is somehow tagged or detected as overlapping speech and is excluded. When you’re working with shorter recordings that don’t have a lot of data to begin with, it would be nice to recover that data.

So, we introduce source separation. It’s an algorithm that takes in a single audio file containing speech from multiple speakers, and split it up into different audio files, one for each speaker. It detects when each speaker is talking (aka diarization) and then uses fancy models to separate the speakers from each other. In theory, this is a great way to recover data that would have otherwise been excluded.

The purpose of this paper then is to see whether such source separation models can feasibly be incorporated into a sociophonetic pipeline. In other words, is the output of a source separation model reliable enough that we can trust the formant measurements that come from the separated audio?

We decided to stress test the method. We took some audio I collected in grad school of two speakers, a man and a woman from Georgia. On separate occasions, they both read 300 sentences in a sound booth. We then overlayed that audio to create a very cacophonous audio file of the two of them talking at the same time for 30 minutes.

We then used three source separation models to separate the two speakers: Libri2, Whamr, and WSJ02. This created six new audio files, one for each speaker and for each model. Combine those with the two original audio files, and we had eight.

For each of the eight files, we sent them through a typical sociophonetic pipeline. First, the originals were manually transcribed at the utterance-level and we used those transcriptions for the their respective derived source-separated audio. We then sent the audio and transcriptions through DARLA to have them force-aligned with MFA and formant-extracted with FAVE. We then followed the same order of operations to process them. In the end, we had four versions of spreadsheets of formant measurements for each speaker’s audio recording. We could then compare them to each other.

First, while coming through the audio, we noticed that two of the models did a pretty good job. But one, the WSJ02 didn’t. We don’t really recommend that one.

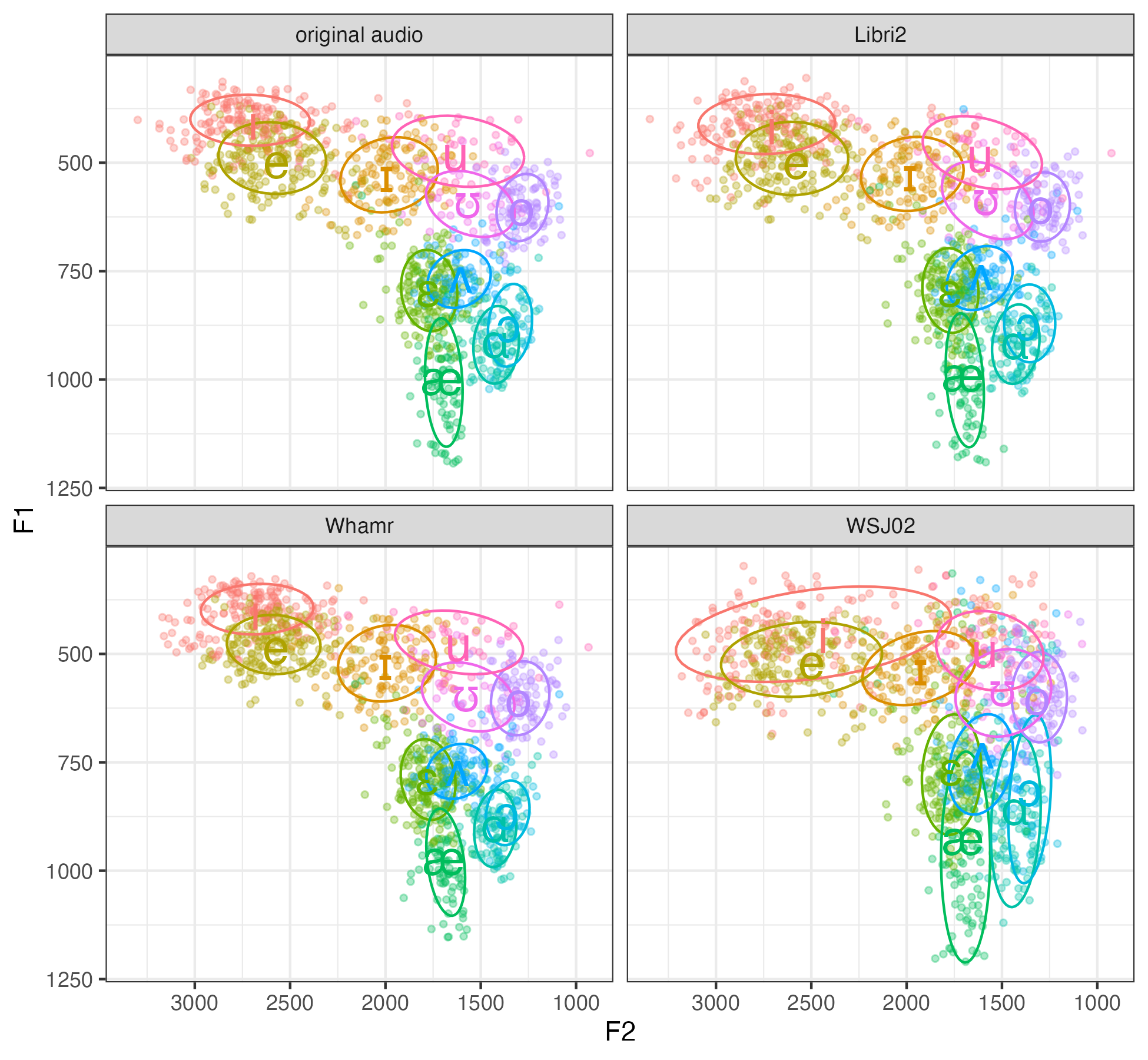

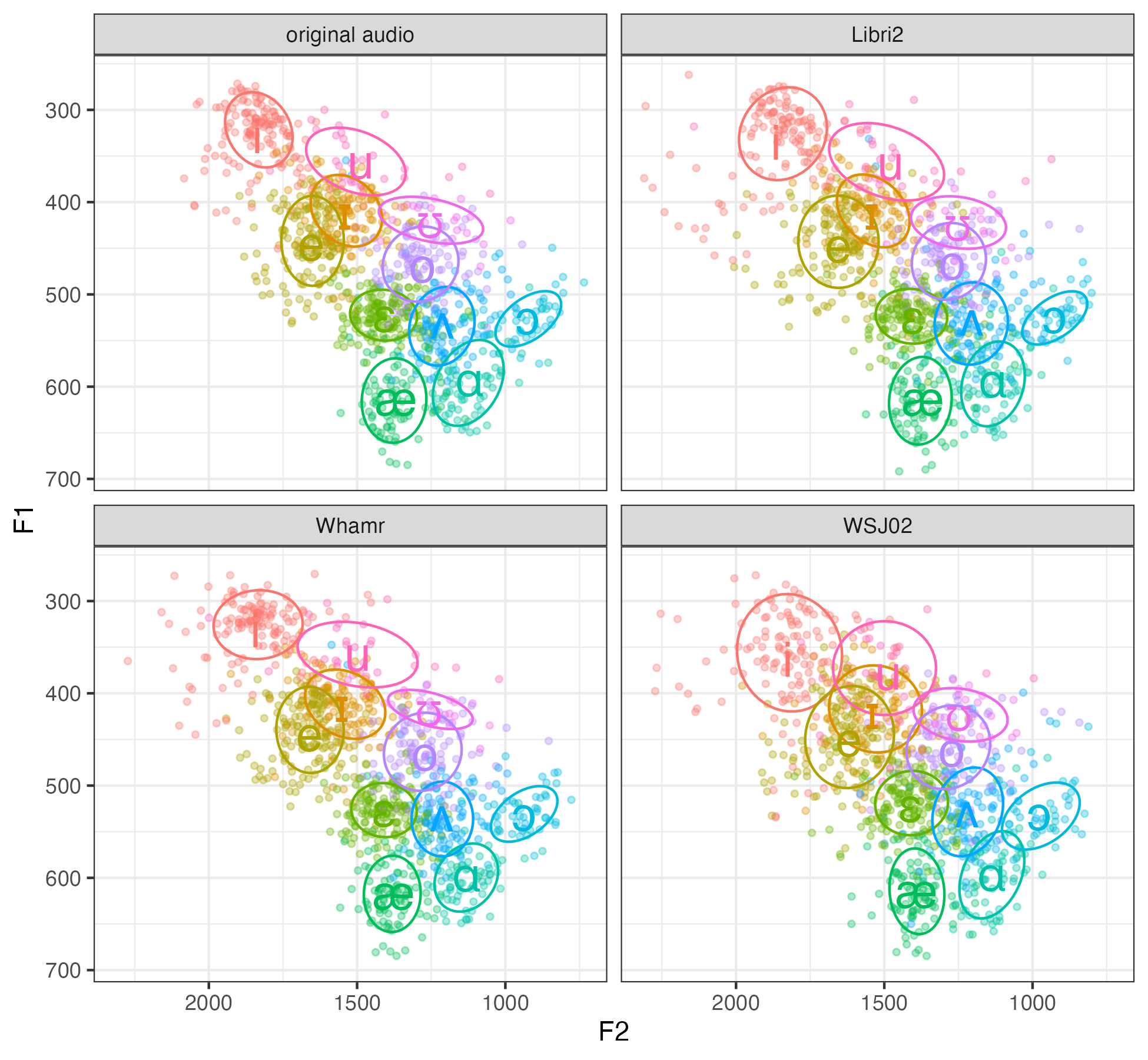

Looking through the vowel plots, we’re surprised at how good they were, especially compared to the original. In these vowel plots (the female is on the left and the male is on the right), all four panels look pretty similar for the most part, and they all look like the top left panel which has the original audio.

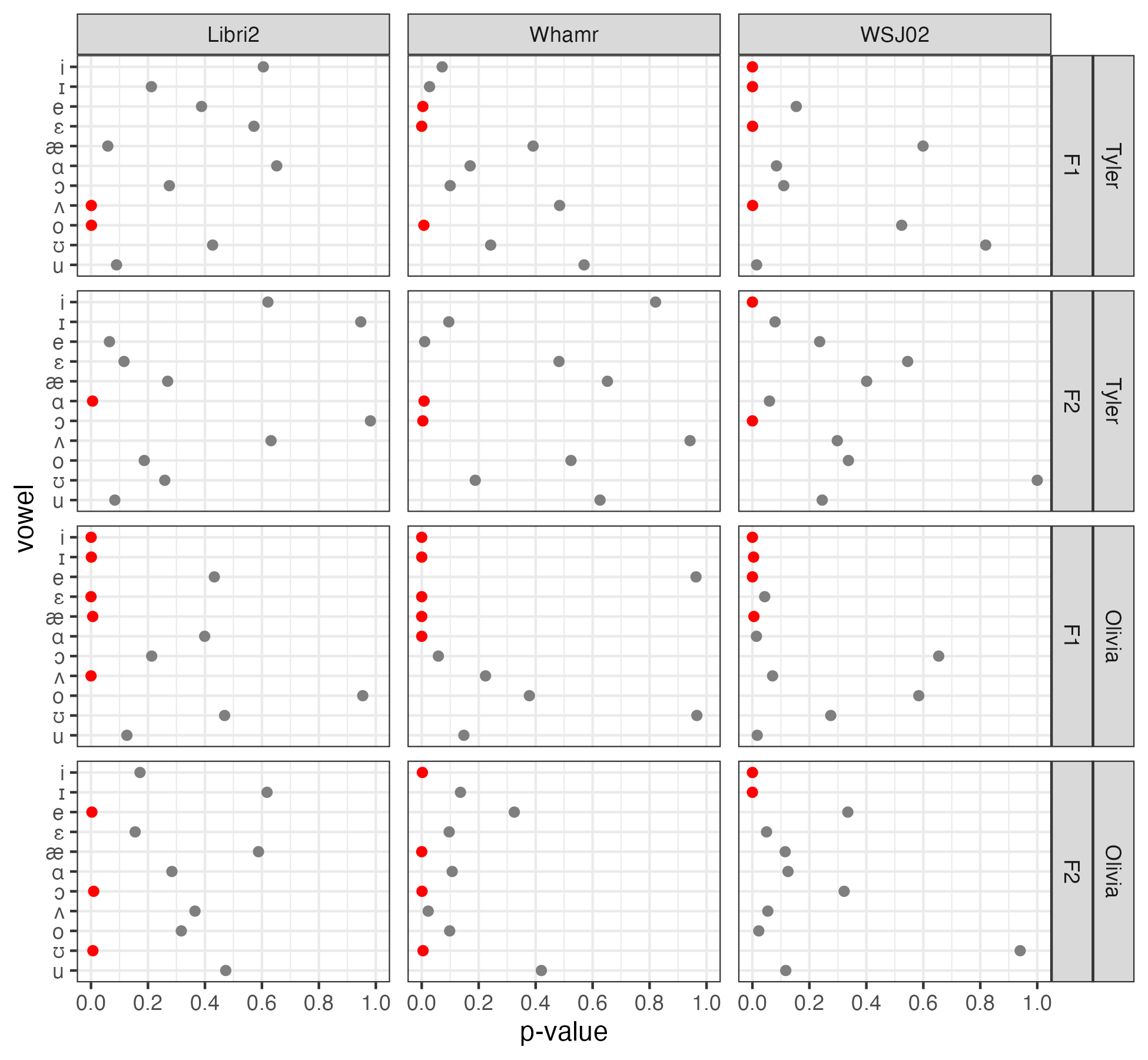

However, when we ran statistical tests on the formant data and compared them to the original, there were some statistically significant differences. But thy varied depending on the vowel, the model, and the speaker. In this plot, red dots are statistically significant differences. But there are many gray dots, meaning the difference between the source-separated audio and the original was not significant much of the time.

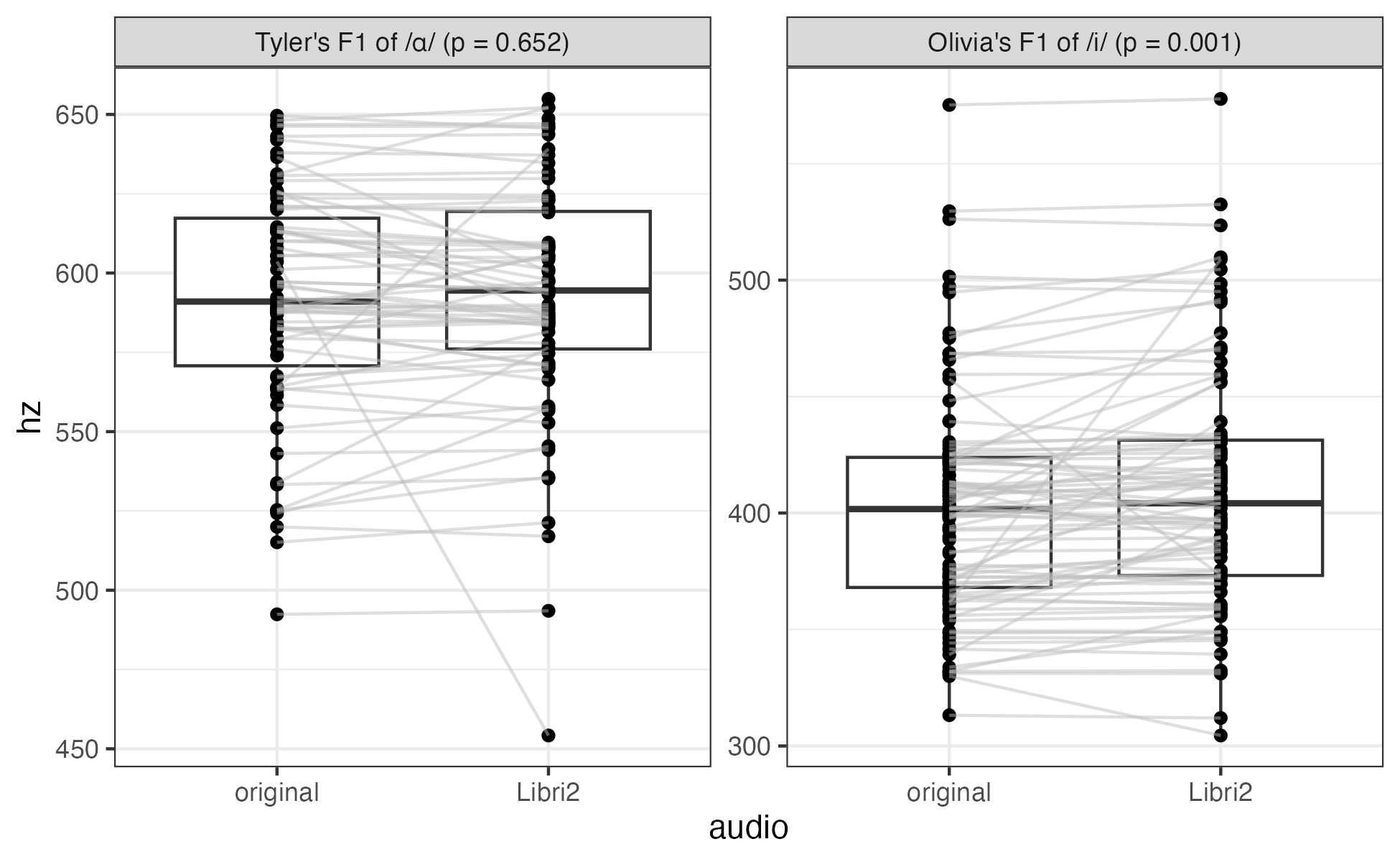

Then when we zero in on specific comparison and then draw lines connecting points that came from the same observation in the two recordings, we see a fair number of differences. So, while the means may be comparable, the values from any one observation may not be close to the original. Thi sis a similar finding to what Strelluf & Gordon report in their book on historical sociophonetics.

So, we are cautiously optimistic about this. If you only model vowel means, you can probably feel comfortable doing so on source-separated data. But if you want to look at individual tokens, maybe not. Fortunately, most audio will not be as overlapped as this, so the effect will be smaller. Although, for dyads of speakers with similar sounding voices, it might not be as good.

We end with some recommendations, which I repeat here:

Experiment with different models to find the one that is most suitable. In this rapidly developing field, models improve over time and new options emerge. So, rather than clinging to one that works, continuously explore potentially better tools.

Split audio at natural breaks rather than equal intervals. This can be done manually or using a script.

Listen to the output to ensure clean separation.

Transcribe based on the source-separated audio or ensure that existing transcriptions still match the new audio before conducting acoustic analysis.

Treat formant estimates at the token level with caution. To be safe, only do analyses on vowel summaries like averages.

Carefully document and report all methodological choices and human interventions.

Backstory

I enjoy learning about papers’ back stories, so here is ours.

May 7, 2024, Lisa and I were talking about this and pitched the idea to Earl. Earl is the one who knows how to implement this stuff, so he worked on it that month and on May 21st, he basically did a proof of concept and said “I think we may have a paper!” In June, we fine-tuned the methods and prepared the audio. We had big plans to do a more robust study with different gender dyads and audio qualities, but we figured for this proof of concept paper, we’d keep it simple. (We may submit a bigger version to JASA still.) By the end of June, we basically had the results we needed, so we submitted an abstract to LSA.

Soon after the abstract was submitted, I figured we might as well write-up the paper. On July 17, I said let’s try and submit to Linguistics Vanguard. For the next week or so, we had a really nice asynchronous collaboration going as we each chipped away at the various parts of the paper we contributed to. (I did the vowel analysis, Lisa did the qualitative analysis, and Earl actual Python scripting). On July 26th, we submitted it!

On October 9th, we got a provisional accept and some useful reviewer comments. Bad timing for us because Lisa and I were about to head to NWAV. But on November 19, we returned the manuscript at 11:54am and at 7:01pm it was officially accepted! Quickest turn-around time ever! We submitted the final version on November 20th, got proofs on January 5th, we presented it at LSA on January 12th, and it was published online on January 29th.

So from inception (May 7) to paper submission (June 26) was 11 weeks. And from original submission to publication (January 29) was 26 weeks. Not too shabby.