My Idiolect

Here is an ongoing description of my idiolect. I add to it whenever I discover new things about the way I speak English.

Overview

I don’t like it when people say they don’t have an accent, however, my pronunciation is pretty close to what I’d call standard American English. I grew up in St. Charles County, Missouri, which is a suburb of St. Louis. You can read Matt Gordon and Chris Strelluf’s work for an in-depth analysis of Missouri English. See also Dan Duncan’s research which is focuses specifically on St. Charles County for an even closer match to my speech. My mom grew up in Minnesota and my dad grew up in Upstate New York and Minnesota.

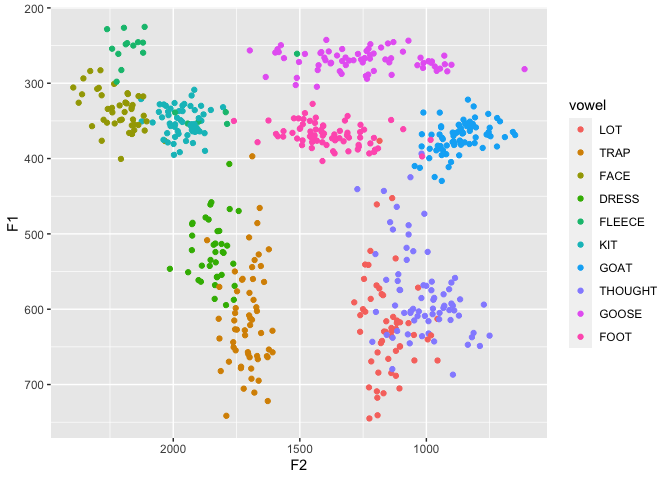

Vowels

Here is a general look at my monophthongs. This comes from a recording of me reading a bunch of real and nonce words where the vowel is flanked by coronals, so there is some co-articulatory effect here.

As far as I can tell, I don’t have really any indication of any of the chain shifts that a lot of sociolinguists are studying. Even though I grew up in the St. Louis Corridor, I don’t have the Northern Cities Shift. I also don’t have the Low-Back-Merger or the Low-Back-Merger Shift.

My low back vowels

My

You can read a fairly comprehensive list of words that I classify as

Like many Americans with the distinction, dog is

Prelaterally, I have a conditioned merger, which is best described in Aaron Dinkin’s (2016) JEngL paper. Historical

As is typical of American English,

One important phonological distinction between my

My CURE lexical set

Like probably most Americans, my

[ɔɹ] (so merged with

force /north ): amour, bourgeois, Bourne, gourd, gourmet, moor, mourn (-ing, -er, -ful, -ed), paramour, parkour, poor, your (when stressed)[uɹ]: allure, boorish, contour, detour, endure (citation form), Fleur, lure, manure, McClure, pleura, tour (-ism, -ing)

[ɚ] (so, merged with

nurse ): adjure, assure, bourbon, caricature, centurion, cesura, courier, during, embouchure, endure (non-citation form), ensure, futurity, Honduras, injure, injurious, insure, jury, jurisdiction, luxurious, mature, Missouri, neural, neuron, plural, rural, spurious, sure, tournament, tourniquet, Ventura[jɚ] (

nurse with a jod): bureau, cure, curious, curate, demure, Euro, Europe, fury (-ious), Huron, manicure, mural, Muriel, obscure (-ity), pedicure, procure, pure (-ify, -ity), Puritan, secure, security, sulfuric, Ural, Uri, urine, Uruguay

And here are words that I saw going through lists of

/æ/ and /ɛ/ before nasals

I raise /æ/ before nasals (i.e. the nasal short-a system). Before /n/ and /m/, it’s raised, fronted, and nasalized, such that ban is definitely not the same as bat or bad. Before /ŋ/, it’s raised even higher to the point that naive me would classify the vowel in bang as /eɪ/. In fact, I’m not actually 100% convinced that it even is /æ/ underlyingly; I may have rephonologized it as being truly /e/.

As I point out on page 74 of my dissertation, there are very few words with /ɛŋ/. A nearly complete list, as far as I know, is length, lengthen, strength, strengthen, penguin, dengue, and Bengal (tiger). For what it’s worth, those vowels are the same as /æŋ/, so that bang and the first syllable of Bengal are the same for me.

beg-raising

As I explain on page 400 of my 2022 American Speech paper on prevelar raising, I raise historic (or perhaps underlying) /ɛɡ/ to something like [eɪɡ] such that beg, egg, leg, and Greg all rhyme with vague. It happens in open syllables like in legacy, negative, and megaphone. It occurs in some infrequent words like renege. I’ve also got it when the vowel has secondary stress, like in Winnipeg, stegosaurus, and nutmeg.

However, there are a handful of exceptions, which was a major part of the reason why I did that paper in the first place. For an unclear reason to me, integrity, segregate, interregnum, and segment all have [ɛ]. I noticed that the /ɡ/ in those words are all followed by sonorants, but that’s not a guarantee blocker of raising since regulate, pregnant, and segue are raised. Interestingly, negligible is raised but negligent is not. Also, peg is raised but JPEG is not. Finally, any word with <x> pronounced as [ɡz] (yes, it’s voiced for me) like exit, exile, excerpt, and exigence are firmly [ɛ] and not [e].

Rosa’s Roses

I don’t know the technical term for this, but I have two, possibly three, unstressed vowels, such that Rosa’s and roses aren’t homophonous to me. The first has [ə] while the second is what I’d transcribe as [ɨ].

My [ɨ] category of words is rather large and I have it in a handful of environments. Some of the distribution is predictable. I have [ɨ] in plurals (classes, offices), 3rd person singular (loses, pushes), and past tense allomorphs (waited, decided). Word-finally, it’s always [ə], as in extra, area, and data.

In a lot of words, I think I’m influenced by spelling. Word-initially, if it’s spelled with an <a>, <o>, <u> I have [ə], as in again, among, and ago, in occur, opinion, and obtain, and in upon, unless, until. (This spelling preference might explain why I always have [ə] word-finally because as far as I can tell <a> is the only letter used for unstressed word-final vowels.) However, if it’s an <e>, then I have [ɨ], as in expect, edition, effect, emotion, event, and exactly.

Word-internally though, I haven’t done enough digging to see if there are any patterns and I’m not familiar with the literature so I don’t know what to look out for. I have a suspicion that if it’s next to a coronal sound, the vowel is [ɨ] and [ə] otherwise. So I have [ɨ] in student, woman, and happen but [ə] in problem, system, and item. I have [ɨ] in minute, private, and unit, but [ə] in product, democrat, develop, and proposal. Interestingly, I have both vowels in advocate [ˈædvəkɨt]. But there are exceptions to these generalizations, like stomach, perfect, galaxy, miracle, and obstacle all have [ɨ]. I have [ɨ] in regime but [ə] in machine, which makes me think spelling is a stronger factor than phonological context. Without being too exhaustive, I’m inclined to think that [ɨ] is the elsewhere allophone and that [ə] is the exception.

As for a possible third one, I have some [ʊ]-like vowel in words like success, support, and suggest. It seems like word-initial <su> might be the environment, but I also get it in to. I’ll have to dig a little deeper to think of other examples.

Prelaterals

I have lost the ability to intuit what’s going on with my back vowels before laterals, but I’ll explain what I think I have. I know I merge /ʊl/ with /ol/, so that pull and pole are homophonous. However, it’s the /ʌl/ class that is really tricky for me. When it’s in a closed syllable, like in hull, dull, cull, and mulch, I’m pretty sure I at least had it merged with /ol/. However, I’ve looked at the list of words so much and I’ve thought about this enough that I pretty much know all the words that fall into this category without thinking (at least the one-syllable words) and I apparently want to unmerge them, so now you’ll be hard pressed to find me saying hull the same as hole, even in casual situations. Words like culture, result, vulnerable, multiple, and ultimately, I have no idea what I do.

In fact, it was this homophone that got me interested in prelaterals in the first place! There is a small town near the University of Georgia named Hull, and I had to go there for something. I thought to myself over and over as a I drove there, “Wait, is this pronounced like Hole?” I never did really figure out what I did.

However, when it’s in an open syllable, like color, gullet, and sculley, it’s usually not raised. The word adult fits in this category as being firmly [ʌ] rather than [o]. Though not all open syllable words are [ʌ] because like gully and mulligan I think I said as [o] when I was younger. (Not sure what I do now.) A word like sullen could go either way, even now.

American Raising

American Raising is raising the nucleus of

I was intrigued by Moreton’s (2021)1 very detailed breakdown of environments for this raising, so I thought I’d see areas where interactions with stress, syllable boundaries, and morpheme boundaries breakdown the simple voicing distinction. Rather than listing all the words though, I’ll summarize and say that /aɪ/ becomes [əɪ] before voiceless consonants including

1 Moreton, Elliott. 2021. Phonological Abstractness In English Diphthong Raising. In Stuart Davis & Kelly Berkson (eds.), The Publication of the American Dialect Society, vol. 106, 13–44. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

monomorphemic, monosyllabic words (as in write and wife)

monomorphemic, polysyllabic words where the next syllable is unstressed (e.g. crisis, bison), except in Eiffel, Micah, Titus

polymorphemic words where the /aɪC/ is tautomorphemic (e.g. flight attendant, wiper, citee)

but not…

in monomorphemic words where the next syllable is not unstressed (e.g. icon, tycoon), except in criteria

if the /aɪC/ straddles a morpheme boundary (e.g. high school, ith, trichromatic, and antisocial), except bicycle (and ice cream).

For whatever reason, I also have the raised vowel in a pre-voiced environments in tiny and tired (which makes any tired-wired jokes and tire-tired puns not always land with me).

/aɹ/-raising

Something I noticed in 2017 and wrote about in a blog post is that the same kind of allophony that I have in

2 Of course, the same shortening rule applies across the board before voiceless sounds.

And again, when that voiceless sound is voiced through another phonological rule like tapping, I get nice minimal pairs like hearty-Hardy and carted-carded. Although, this might only be noticeable if I have access to a voiceless sound in an underived from, because as I was going through words that fit this phonological frame, I realized that I have a lower vowel in Marty and martyr.

In addition, if

However, there is certainly some variation, and I’m not entirely sure what drives it. Words like garlic, garbage, garb, garble, gargoyle, garment, garner, and garnish all have the lower vowel. Perhaps most strangely, Garfunkel has the lower vowel, even though (like Garfield), it has two reasons to be raised.

Other things

Phonological

Systematic things

/t/ and /d/ before /ɹ/ (as in try, train, dry, and drain) are affricated to [ṯ͡ʃɹ] and [ḏ͡ʒɹ]. In other words, little kid me would spell them as “chry” and “jrain”.

In words like mountain, button, and satin which have /tən/ following a stressed syllable, I typically pronounce them with a glottal stop and a syllabic nasal: [bʌʔn̩]. There are some exceptions though, like sentence, which I can pronounce that way but typically use [tʰɨn]. In cases where the /tən/ is not immediately following the stressed syllable, there’s some inconsistency. For example, militancy firmly has [tʰɨn], competent and hesitant have a flap, and while I typically say bulletin and Samaritan with [tʰɨn], I could see myself using [ʔn̩] in informal contexts.

I pronounce the <l> in words like psalm, alm, palm, qualm. I also pronounce it in wolf, yolk, and folk. I know I used to insert an [ɫ] in both and local, but I don’t think I do that anymore. I do do it in only though.

Though both my parents grew up north of the “on line” (i.e. the North-Midland boundary) and therefore have

lot in on, I don’t, so on is firmlythought .

Idiosyncratic things

I epenthesize a [k] in ancient, [ẽɪ̃ŋkʃɨnt]. I think what’s going on is I have [ŋ] instead of [n] in the first syllable, possibly analogous to anxious, and the [k] slips in there as I transition from the velar nasal to the post-alveolar fricative.

big has a bit of raising towards the end of the vowel. I’d transcribe it as [bɪi̯ɡ]. I don’t have it in any other /ɪɡ/ word, as far as I know, not even pig.

want is [wʌnt]. So, wants is homophonous with once.

I 100% say camouflage as “camel-flage”. So I have an extra /l/ in there.

The last syllable of kindergarten has a /d/ underlyingly rather than /t/.

The default way I say grandma is [ɡɹæ̃mə].

The second syllable of caterpiller doesn’t have an /ɹ/ underlyingly: /kætəpɪlɚ/

lair is homophonous with layer and does not rhyme with hair.

I don’t have the pin-pen merger, but I have a few exceptions like /ɪ/ in parentheses, embed, and enchalada and /ɛ/ in symmetry.

I consistently say settler with three syllables ([sɛ.ɾl̩.ɚ]) and not two (*[sɛʔ.lɚ]), even when saying the name of the game Settlers of Catan.

I think I say violet with two syllables, meaning it’s [ˈvɑɪ.lɨt] instead of [ˈvɑɪ.ə.lət]. However, alveolar does have a very short schwa, so it’s [æɫˈvi.ə.lɚ], which does not rhyme with velar [ˈvi.lɚ].

I say the final syllable of astronaut with

lot , as if it were “astro-not,” rather than the probably more etymologically accuratethought , as if it were “astro-naught.” I do say nautical withthought , so I think this is just a quirk about this one word.I say cough drop both with

thought /kɔf drɔp/ rather than /kɔf drɑp/ withlot in drop. Probably some sort of vowel harmony analogy thing because I otherwise say drop withlot .I say uniformly as if it were spelled “uni-formally”.

Grammatical

Even though I grew up in the Midwest, I do not have needs washed or positive anymore.

I’m not a native user of double modals, but I’ve started using might should.

I can say ones after plural demonstratives these ones. I think I might have it after full NP possessors, like Charlie’s ones, but I don’t think I have it after pronouns like my ones. There’s probably some nuance there I need to explore.

My default second person plural pronoun is you guys, even when addressing a group of women. The genetive form is the doubly marked your guys’s (or however it’s spelled).

Lexical

I call a frontage road an outer road. Apparently this is a uniquely Missourian thing to do.

I don’t have the word freeway in my native dialect. I use the term highway instead to refer to an interstate. But, confusingly, I also use the term highway to certain larger primary in-town roads (i.e. at least two lanes in each direction and a speed limit of at least 45 mph) as well as to some two-lane outskirts-of-town kind of roads. This has lead to occasional confusion because the town I live in has an interstate on one side and a large road on the other side and while most people refer to them respectfully as freeway and highway, I call them both highway. So, when I said I live “close to the highway”, it was unclear to the listener.

I say kitty-corner, roundabout, firefly, drinking fountain, and soda.

I say crayon as /kɹæn/. I say gif as /dʒɪf/. I say often as /ɔfɨn/.

I don’t know if I say crayfish or crawdads because I had never heard of those before hearing about them in dialect quizzes.

My kids’ speech

Since my kids are growing up in an area different from where I grew up, they will likely acquire a different variety of English from my own. Here’s a list of things I’ve heard my 9-year-old kid says that is different from my own speech.

kindergarten has a clear [t], i.e [kʰɨndɚɡɑɹtʰɨn] while I definitely have an underlying /d/ there.

The full cot-caught merger, though she had that before she started school. In New England at least, Dan Johnson found that when a child’s mother is merged, “a distinct father may actually make girls more merged” (2000:79).

Occasional use of [ʔɨn] in words like Martin.

Occasional lowering of /il/ to [ɪɫ] in words like feel and lowering of /el/ to [ɛɫ] in words like veil.

Occasionally inserting a velar stop after /ŋ/ as in [sɪ̃ŋk] sing.

As for my 5-year-old, he inserted a [t] in Wil[t]son within a week of starting kindergarten, though I haven’t seen that spread to other words.